My Braille Beginning

Door. Wall. Washbasin. Chair. Trampoline.

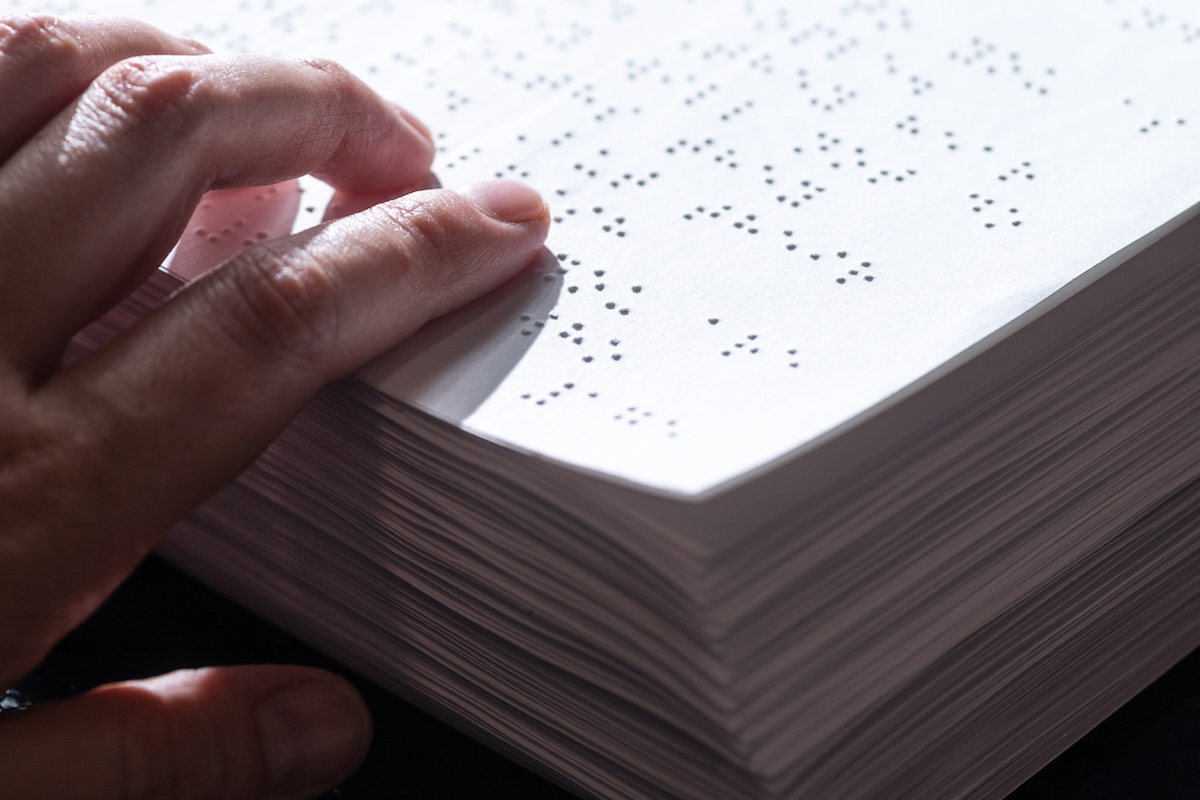

Sticky Braille labels attached to the relevant structures in the house were my first introduction to Braille. Some well-meaning professional had obviously told my parents to label things, even though I was still only about one year old — and knew very well what the trampoline was, considering it was one of my favourite activities.

I may not have known that the first clump of dots, melted and faded as they were by the elements, was a T for the start of trampoline. But I knew that combination of blobs in its entirety was the word that represented the big bouncy mat that was great in summer to put the hose under.

I never questioned that I would learn Braille.

I knew those who were not blind used written shapes my Mum called “sighted writing”, but I knew Braille was for me. I knew Braille was how I was going to be able to read books — and I loved books from the day I knew what one was.

Why Braille Isn’t Optional

Today, I am still a great book lover — from thrillers to family dramas, autobiographies to political essays. I may use technology instead of paper now, but all of these books are made available to me thanks to Braille.

And this is where we have a myth to bust.

Not all people who are blind read Braille. It is not the universal language of the blind — the communication barrier breaker that enables us to live on an equal footing with the sighted. I think it should be, but that is not reality.

With the proliferation of audiobooks and synthetic speech, such as that available in screen readers, I have found a lot of people dismiss Braille as “just all too hard”.

Why labour over dot position, contractions, word signs and preferred Braille displays when a friendly — if robotic at times — voice can read something to me?

Why take a book away and carry large volumes or an expensive Braille display on the plane when I can just stick my earbuds in and zone out with a good narrator?

Here is why.

Braille Is Literacy

By having someone read you the news or a good book, you are gaining the information — but you are not experiencing it for yourself.

How can you imagine a character in a story when the narrator gives their interpretation through their voice?

How can you learn to spell when you have never seen a word in front of you, only heard it spoken?

I am not saying audiobooks, screen readers and the like do not have a place. They absolutely do. In fact, I am using a screen reader to write this article — and my Braille display is somewhere in the lounge room (I think!).

But choosing to forgo Braille for convenience locks you out of a world of knowledge, information, enjoyment and — yes — beauty.

The texture of Braille under the fingertips is beautiful. A tactile artwork.

Low Vision Kids Deserve Braille Too

Here’s another issue: children with low vision are often denied Braille because it’s seen as the domain of the completely blind.

The sighted world would rather have a child struggle with giant print — face pressed to the page — than teach them Braille. Why? Because print is “normal”, and Braille marks you as officially disabled.

As if that’s something to avoid at all costs.

If the child was taught Braille, their academic achievements, speed and emotional wellbeing may improve. But that doesn’t matter, because teaching Braille would make the child part of the “Blind” club — that other world that is “abnormal” and officially in the domain of the disabled.

And what, may I ask, is wrong with the “blind club”?

Let’s Celebrate Braille

Braille is officially not a language — but in my opinion, it should be. That is why I always capitalise Braille, to give it the respect it deserves.

Braille opens a world of language, words, knowledge, beauty and connection. It enhances prospects for employment, increases educational opportunities and enables greater independence.

Who doesn’t want to be more effective at their job, do better at school, or be able to navigate the kitchen independently?

All of these reasons are why I firmly believe Braille is sacred.

We need to protect it.

We need to love it.

We need to celebrate it for the great equaliser it is — and most importantly, promote it.

When you meet someone, don’t assume they read Braille — chances are they won’t.

If you do read Braille, don’t expect to see much of it in the community.

But let’s change that.

Let’s get Braille’s name out there once and for all.

Let’s make Braille go viral.